Blog from the bog - Trees are good but bog is better

The Marches Mosses Bog LIFE project aims to restore Britain’s third-largest lowland raised bog within the Fenn’s, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses and Wem Moss National Nature Reserves (NNRs) near Whitchurch, Shropshire and Wrexham in Wales.

The project is led by Natural England working in partnership with Natural Resources Wales and the Shropshire Wildlife Trust. The multi-million-pound five-year project is supported by an EU LIFE grant.

Here Mike Crawshaw, Engagement Officer for the project explains how protecting a 10,000-year-old habitat involves the removal of trees, and how this is done with minimal impact.

Fenn’s, Whixall, Bettisfield, Wem and Cadney Mosses – collectively known as the Marches Mosses, together form the third largest lowland raised bog in the UK. The Marches Mosses straddles England and Wales, with 75% of the NNR in Wales.

Protecting a rare habitat

The Marches Mosses started life at the end of the last Ice Age approximately 10,000 years ago. Over this time the peat has built up over millennia as a result of the bog vegetation being annually ‘pickled’, giving rise to the special habitat we see today.

Bogs are characterised by being open landscapes covered with specially adapted vegetation such as sphagnum mosses, cotton grasses and sundews. These plants thrive in the very wet and nutrient poor conditions found on a bog.

Sphagnum acts as a ‘keystone species’ actively encouraging water retention, high acidity and peat forming. This results in conditions that are unfavourable for trees to grow. So, healthy bogs are open areas with a scattering of scrub and trees and wouldn’t naturally be covered by woodland.

However, on the mosses the large number of ditches and drains found across the bog has dried out the surface allowing trees to self-seed, establish and thrive.

On other parts of the bog conifer plantations were planted relatively recently in the 1960’s. As such nearly all the wooded areas on the mosses are of relatively recent origins and none are ancient or protected.

Whilst typically trees and woods are important in the countryside and to be encouraged, on a bog their large numbers are damaging to the delicate ecosystem of the habitat.

The deep roots and large leaf canopy of trees act like water ‘chimneys’, sucking large amounts of water out of the ground (up to 30% of the water table) which in turn makes the ground even drier.

Gradually, once the trees become dominant, the bog vegetation and rare specialist species beneath that have been present for thousands of years decline and disappear.

Removing trees

Nationally 94% of the lowland raised bogs have been lost. Fortunately, Fenn’s and Whixall Mosses represents one of the best remaining examples, albeit damaged, of this rare habitat in the UK.

However, the good news is that bogs are resilient and over the past 30 years there has been considerable progress in repairing past damage and restoring now flourishing areas of natural bog habitat.

To repair some parts of the mosses we have had to undertake the managed, selective removal of trees and wooded areas which have established over the past 30-60 years.

This work also involved creating ‘bunds’ on the peatland. These are banks of peat that act like dams to hold water on the surface of the bog. This work will restore squelchy boggy conditions vital for the recovery of bog plants and sphagnum mosses.

How is tree removal undertaken with the least impact?

Decisions on tree removal are carefully considered and planned. Each area is assessed by ecologists in the team looking at both the existing species records for an area and the potential of an area to be restored as bog habitat.

The latter is informed by peat depth survey information to assess if the water retention technique of ‘bunding’ is suitable.

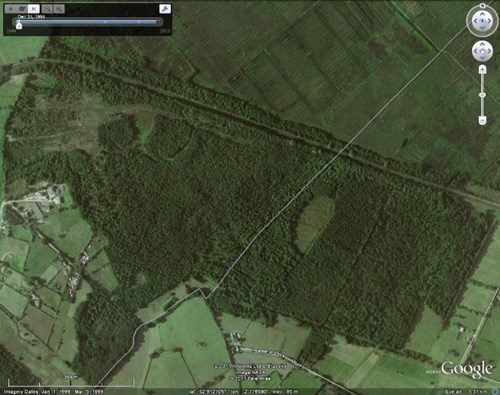

Bunding uses deeper, water retaining peat to make a 30cm tall bund that will hold back rainwater in a “cell” (see below aerial image showing the bunding cells).

This allows the degraded peat within the cell to rewet and ‘re-pickle’. The process of digging down to the water retaining ‘good’ peat also breaks up any underground water drainage channels, meaning that water is stopped from draining away both above and below ground.

Image above - aerial view of the bunding cells on the Marches Mosses (credit Natural England).

In selected edge locations with shallow peat, the bunding will encourage development of wet woodland. This rare habitat would naturally have occurred at the edge of the bog in the past.

Where appropriate, a margin of trees is retained around the felling areas to help provide a weather and landscape buffer and to serve as a wildlife link between retained wooded areas (see images below).

Many of the drier sandy areas on the edge of the nature reserve have also been left to regenerate to scrub and woodland over-time.

Image above – Bettisfield Moss – left aerial image shows the site before restoration and right aerial image shows the same site after restoration with a margin of trees (credit Natural England).

Bettisfield Moss is an example of formerly wooded area successfully restored (see images below). The open area you see today was formerly a conifer plantation.

The trees were harvested around 20 years ago and the bunding works have taken place over the past three years. Today it is covered by flourishing high quality bog vegetation and home to some of the rarest species on the nature reserve.

Image above – Bettisfield Moss was formerly a conifer plantation (left) and today (right) it is a healthy and thriving bog habitat (credit Natural England).

As Fenn’s, Whixall and Bettisfield NNR is the third largest lowland bog in the UK, it is a nationally important stronghold for wildlife like the large heath butterfly, the white-faced darter, and curlew, many of which are struggling nationally.

As well as benefiting the important bog plants, removing trees will also benefit these species by returning degraded areas of bog back to a healthy state that these species can once again call home.

Therefore, where trees are removed and the peat is rewetted, this will over time reset the active process of peat accumulation and carbon storage of the habitat.

Each acre of bog at Fenn’s and Whixall Mosses contains 15 times the amount of carbon than the equivalent area of mature woodland. It is estimated that an enormous 3 million tonnes of carbon is locked in the peat at Fenn’s and Whixall Mosses.

The important function of the mosses as, arguably, one of the region’s largest natural carbon sinks is being maximised enabling it to play an important role in mitigating the impact of climate change.

To find out more about the Marches Mosses Bog LIFE project please visit the website or follow them on Facebook @MarchesMossesBogLIFE or on Twitter @MeresandMosses.